Why It’s So Hard to Build a Human Brain

Preface

I wrote this article in the fall of 2021 as a piece for the Medium Blog of Neurotechnology@Berkeley. You can find other articles I authored/co-authored there, too, and I will slowly start moving the better ones onto here. I thought I would start with this one. Credits go to Andrew Lin and Luc LaMontagne for assisting the writing and editing process.

What follows is a (now dated) set of thoughts on AI. I say dated because a lot has happened in the last year and a half AI wise, and I’ve also learned a lot more. I’m not revising the thoughts presented here to preserve some of the originality of the writing, so that I can come back and review how my thinking has evolved. Also, I’m too lazy to rewrite this.

This is also my first post on the site, so I thought hard about choosing which article to use. I settled on this one because I think its a good introduction to the direction I hope this blog/collection takes.

Why is it so hard to build a human brain?

Now there’s a tough question to ask. Biologists, neuroscientists, and computer scientists will all give you slightly different answers, but in the end, one theme unites them: the brain is really, really, really complex.

Biology has made progress in brain-building — in late 2020, scientists at Cambridge [announced] (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41593-021-00923-4) they had grown artificial tissues known as organoids that behaved neurobiologically like brain tissue. This step marks a milestone for understanding how the brain develops over the course of a lifespan since we can now learn from “test-tube brains”.

Computer scientists tell a different story, one of AI and the push to recapitulate human intelligence in computer programs. Efforts here have been fruitful, but progress is slowing. To truly build a human brain needs a little bit of something we don’t have yet — new knowledge about the brain, its parts, and the mysterious ways it works.

The old days of neuroscience: what have we learned so far?

Psychologists, neurobiologists, physicians, and neuroscientists alike were once most interested in understanding the brain as a human organ. How does a lump of pink flesh autonomously control most of our daily functions, while also serving as a center for conscious thought, communication, and memory storage? There was (and still is) so much we didn’t know about the brain.

At a time when technology like fMRI was unavailable, and locations of the brain could not be directly mapped to physiological functions, the brain was essentially a black box. We knew nothing about it — only that it took input signals from the rest of the body and coordinated output signals to control the body’s responses.

As neurotechnology progressed over the last century, we began to get clearer pictures of the brain, its physiology, and its many mysteries. The more we learn, the more we realize we didn’t know before. Where does conscious thought originate? How does neural architecture give way to the complex cognitive processes we employ each and every day?

There’s research underway to get at the heart of some of these questions. One such project is a spinoff of the famous Human Genome Project, called the Human Connectome Project (HCP). In a collaborative effort, the HCP hopes to map each and every neural connection in the adult human brain, thereby building a complete electrophysiological map of the brain that can be used to answer some of the outstanding questions we have. But we’re lightyears away from that reality — only one organism’s connectome has been fully mapped: C. elegans (a roundworm), with only around 300 neurons. The human brain has almost a billion times as many. Fully mapping the human connectome will likely take an incredible amount of time, but armed with key information about the complete human neural architecture we might be ready to take our first steps towards reconstructing a brain in a lab.

Black Boxes and the Computing Revolution

The AI community has taken a slightly different approach to understand intelligence. Rather than study the brain as it is, they ask whether they can create their own version of one using what we know about brains so far. Using key principles from neuropsychology about learning and memory, computer scientists try to construct programs that mirror what we know about brain architecture and let these programs learn from data to build some sort of intelligence. In this way, they treat the brain as a black box.

Black boxes are systems that we know nothing about internally, except for a set of inputs and their outputs. Try as we might, black boxes are often far too complicated to decipher. With 86 billion neurons, it is certain the brain has an architecture far more complex than can ever be imagined. However, we know with reliable accuracy how to predict brain outputs based on inputs. We know that when certain external stimuli are presented to an individual, different areas of the brain may light up on an fMRI, indicating a wide variety of neural responses.

Though it may, in many cases, suffice to describe black boxes merely in terms of their input-output properties, that just doesn’t always cut it. This problem has some interesting implications for both the neuroscience and AI communities that I’ll touch on soon.

Computers were originally built to help humans solve hard problems faster. We would do the thinking, and they would do the hard number crunching. But a paradigm shift took hold late in the 1900s when we decided computers should be able to think as we do — that would solve hard problems even faster. We wanted them to learn. We wanted them to approach problems the way a human would, not the way a machine would. And so we trained them and designed them to learn, and now we have algorithms that do just that. In just the last few decades, progress in fields such as machine learning and artificial intelligence has skyrocketed as we seek to reconstruct conscious, intelligent processing outside of the human brain.

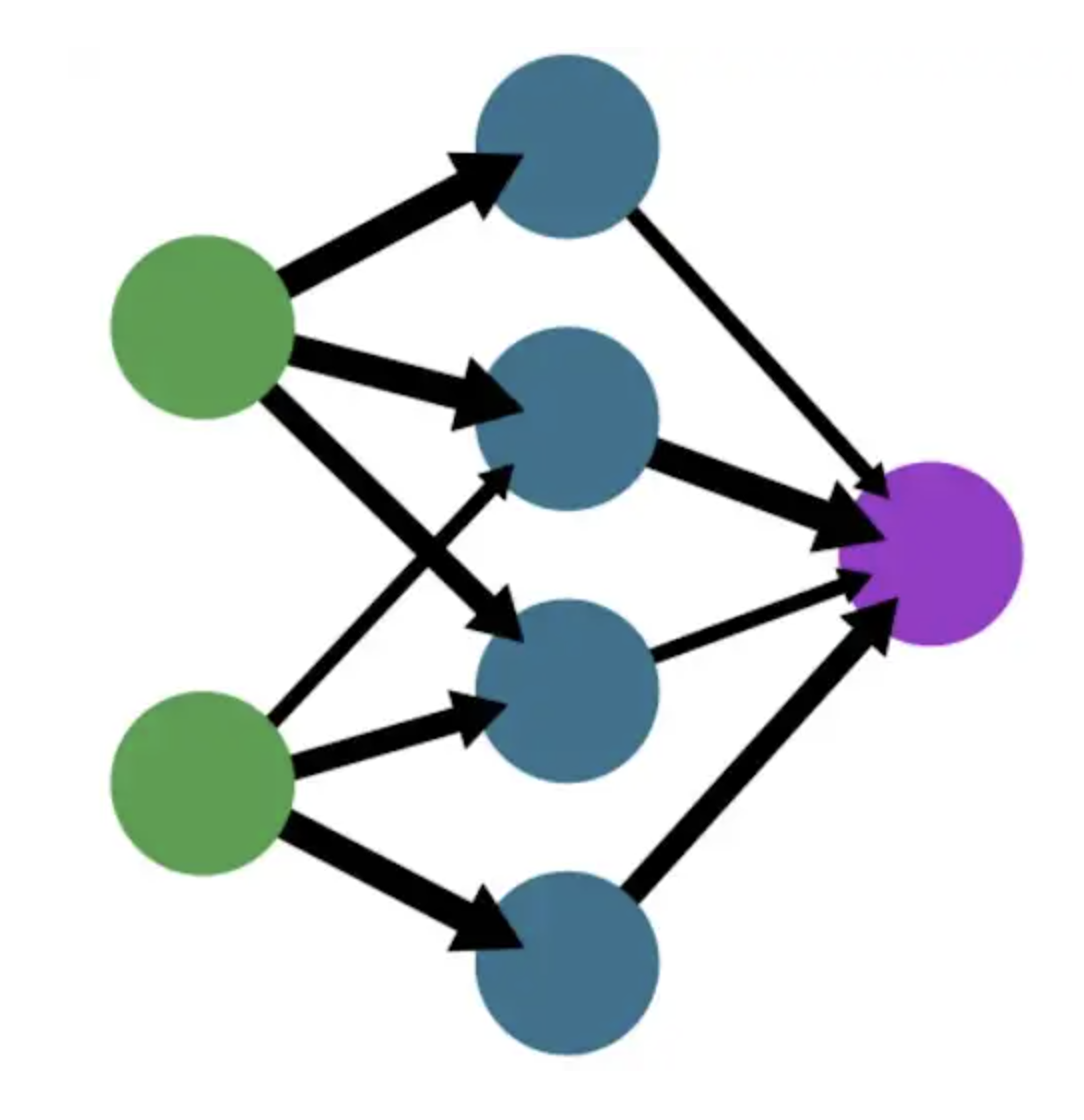

Many of these learning algorithms use neural networks like the one diagrammed below. These are computational structures designed to mimic the neural architecture of the brain itself. Below is an example of such a neural network, which takes in some inputs externally (shown in green), feeds them through several rounds of computation and evaluation (shown in blue), and returns an output (shown in purple).

The combination of many different inputs and several layers of intermediate computation give rise to “deep” learning. These networks can be shown in similar ways to the simple network above but would have many parallel layers of blue intermediate “neurons” that assist with processing. Deep learning algorithms were once a thing of fiction, but have now been used to do small tasks such as image classification and description. What’s far more interesting than their computational power is their similarity to the brain itself. Deep learning networks are not as sophisticated as the human brain, but they have been shown to behave in similar ways. Research has shown that certain deep learning models can potentially serve as elementary representations of the sensory cortex, the set of brain regions involved in processing sensation. In short, deep learning algorithms can process visual information in a very similar way to how human brains do.

So it’s clear we’re making headway in this field. But still, we have to ask the question: when do we get to make real human-like brains?

Not anytime soon…

A rather depressing answer, but true nonetheless. The first step to reconstructing intelligence outside a human body is to develop an algorithm that thinks, learns, and behaves like a human. And the first step to doing that would probably be to figure out how the brain does anything along those lines in the first place.

We’re fairly certain that brains operate like very complicated neural networks, at least for some purposes. They have many layers of computation, are spatially organized, and have an unimaginable number of connections. They are far more complex than any neural network we have programmed. But we might try first to understand the simple neural networks we do have.

Therein lies the problem. The neural networks we do have often behave like black boxes themselves. They take in inputs and put out outputs, but we haven’t the slightest clue what happens in between. We can train these algorithms to work better, but the inner workings are sometimes too complicated for us to decipher.

So we can’t even break down all the simple models we have. On top of that, there is growing evidence that certain features of neural network-based learning algorithms are not found in human brains and vice versa. A key example is the principle of backpropagation. In learning algorithms, we can encode steps that allow the network to adjust itself based on minimizing errors made between predicted and observed outputs. This feedback is called backpropagation and is an essential feature of many different neural network schemes. Interestingly enough, there is no conclusive evidence that such a mechanism is as relevant in the human brain.

Conversely, there are brain features that have not yet been replicated in artificial neural networks. In some ways, it feels like we’ve arrived at the base of an insurmountable problem. Where do we go from here?

Possibly, we won’t ever have the computational power to reconstruct a brain in silico. We may not have the computational power to probe every detail of the brain’s connectome. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t keep trying.

It also doesn’t mean there aren’t other ways of getting to where we want to go. We’re often reminded of the fact that biological evolution is guided entirely by random mutations in our genetic code. We were not designed to have intelligence — it just sort of happened. There was no path to follow, and yet we still ended up right where we are today.

AI will progress in a similar fashion. Guided in part by humans, but evolving on its own, too. Learning models will build on each other and become more sophisticated. Technology will give us unprecedented computing power, allowing us to construct larger and deeper neural networks.

We won’t have built a human brain. But we’ll get just about as close as we can.